The Saga of a Soundtrack

Michael Moynihan

With the advent of the conformist nightmare that consumed most of America in the 1950s, something eventually had to break. By the middle of the following decade, it most certainly had—and the shattered evidence was plain to see. Under a California sun, the shards and splinters of what had been a monochrome world now glinted in Technicolor brilliance, dazzling the eyes of those who dared to look toward new frontiers. The old rules were dispensed with, scorned and abandoned as anachronistic restraints. Dividing lines between art and life melted away, and for a few fleeting moments—or even years—anything seemed possible.

Once the dark mirror reflecting status-quo culture had been shattered and the floodgate opened to an alternate stream of consciousness, there was little controlling what came through it. Those hardier souls possessed of stamina and vision could ride the cresting wave and even channel its rushing forces as a means to propel their own creations. But as one wave rolled in, another was right on its heels—sometimes more disorienting than its predecessor. Many who immersed themselves in this tumultuous tide were soon lost at sea or drowned in unfamiliar waters.

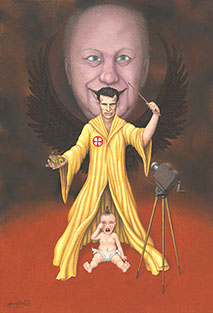

A newfound freedom borne of unrestrained circumstances is invigorating, but not always easy to handle. Trial and error was the only available procedure for processing these experiences, and results could sometimes be fantastically beautiful—or frighteningly disastrous. In the burgeoning youth subculture, chaos increasingly became the rule. In order to navigate the unknown, a torchbearer was needed to guide the way, and preferably one with experience. For the artists Kenneth Anger and Bobby BeauSoleil this torchbearer, capable of illuminating the path to a new dawn, was none other than Lucifer, the rebel angel and “light bringer.”

Anger and BeauSoleil are both magicians—visionaries who harness non-material elements in order to manifest their creative wills. Anger, the filmmaker, works with light, flicker, and shadow; BeauSoleil, the musician, with tone, tempo, and melody. Their individual temperaments are exceedingly distinct, the products of two different generations and widely divergent backgrounds. But upon meeting they immediately recognized in one another the complementary talents, innate energies, and a kindred fate that bound them together. That fate found a name in Lucifer Rising, a legendary film project that would take more than a decade to complete. By the time it was done, the collaborators had each dramatically undergone their own series of trials and tribulations—literally and figuratively.

In early 1967, the nascent socio-cultural revolution was in full swing. Kenneth Anger was living in San Francisco—the eye of psychedelic cyclone—and beginning work on his newest underground film, Lucifer Rising. Anger had already begun dealing with social taboos in earlier films like Scorpio Rising, but this new work would invoke heretical spirituality and serve as an apologia for a denigrated deity. In Anger’s words: “I’m an artist working in Light, and that’s my whole interest, really. Lucifer is the Light God, not the devil, that’s a Christian slander. The devil is always other people’s gods.” For the leading role of the “sun-souled” Lucifer he needed someone who archetypally embodied the spirit of freedom and “joyful disobedience.” He thought he had already found a suitable actor to do the part, but those plans would be quickly revised after Anger attended an unusual event called the “Invisible Circus,” the joint brainchild of Emmet Grogan’s anarcho-activist group, The Diggers, and the Sexual Freedom League.

The Invisible Circus was planned as a continuous “happening” in which the audience would be active participants for a raucous three-day program of music, poetry, theater, and free love. For the location the organizers rented the Glide Memorial, an unusual Methodist community church run by Reverend Cecil Williams and situated in the city’s run-down, red-light district known as the Tenderloin. One of the highlights on the opening night was a performance by nineteen-year-old Bobby BeauSoleil’s “psychedelic chamber orchestra,” The Orkustra. Among its members was violinist David LaFlamme, who later went on to gain considerable recognition with his group It’s A Beautiful Day. The Orkustra used unconventional electrified acoustic instruments to create semi-improvised walls of sound that were as much inspired by classical, jazz, Indian, or Far Eastern music as they were by rock’n’roll. In many respects, the band was far ahead of its time. They were also a perfect complement to the atmosphere of the Invisible Circus, and their undulating music unleashed a tempest of sensuality that night in the densely crowded room. After their performance, the band members retreated outside to the parking lot for fresh air. It was here that Kenneth Anger, having just witnessed The Orkustra’s rapturous show at close range, first approached his potential recruit. He had found the perfect leading man for his film: “You are Lucifer!” he exclaimed to a mystified Bobby BeauSoleil.

The Invisible Circus was planned as a continuous “happening” in which the audience would be active participants for a raucous three-day program of music, poetry, theater, and free love. For the location the organizers rented the Glide Memorial, an unusual Methodist community church run by Reverend Cecil Williams and situated in the city’s run-down, red-light district known as the Tenderloin. One of the highlights on the opening night was a performance by nineteen-year-old Bobby BeauSoleil’s “psychedelic chamber orchestra,” The Orkustra. Among its members was violinist David LaFlamme, who later went on to gain considerable recognition with his group It’s A Beautiful Day. The Orkustra used unconventional electrified acoustic instruments to create semi-improvised walls of sound that were as much inspired by classical, jazz, Indian, or Far Eastern music as they were by rock’n’roll. In many respects, the band was far ahead of its time. They were also a perfect complement to the atmosphere of the Invisible Circus, and their undulating music unleashed a tempest of sensuality that night in the densely crowded room. After their performance, the band members retreated outside to the parking lot for fresh air. It was here that Kenneth Anger, having just witnessed The Orkustra’s rapturous show at close range, first approached his potential recruit. He had found the perfect leading man for his film: “You are Lucifer!” he exclaimed to a mystified Bobby BeauSoleil.

Shortly after listening to Anger’s pitch, BeauSoleil agreed to involve himself in the film—so long as The Orkustra could provide the soundtrack. Anger, in turn, fired his former candidate for the Lucifer role and enthusiastically took BeauSoleil under his wing. Not everyone was happy about the new relationship, however: BeauSoleil’s obsessive dedication to the film project ultimately alienated his band mates and was a factor leading to The Orkustra’s breakup. BeauSoleil was undaunted, however, and set about to assembling a new group to record the soundtrack. Christened The Magick Powerhouse of Oz, the band soon became a sort of underground legend, despite the fact that almost no one ever heard a single note of their music. This reputation came about largely due to circumstances of their existence: they seemed to have solely existed in order to score the music for a dark, Aleister-Crowley-inspired occult underground film. The band’s name was drawn from Crowley’s philosophy of occult “magick” and L. Frank Baum’s Oz novels, with “Powerhouse” being a reference to the surreal constellation of brightly colored wheels, pulleys, and machinery that powered the cable cars of San Francisco, the Emerald City itself.

By this time BeauSoleil had moved in as a housemate with Anger at a creaky Victorian mansion known as the “Russian Embassy” and perched on the uppermost corner of Alamo Square. A contemporary photo taken inside the house shows BeauSoleil sitting center-stage and holding his electrified bouzouki, the number 666 emblazoned on the chair back above him, surrounded on either side by the motley members of the Magick Powerhouse. While their collective reputation lives on, the names of these musicians—street performers of various stripes whom BeauSoleil had discovered at neighborhood corners and cafés—have long been forgotten.

That summer a new venue, The Straight Theater, was being renovated in the Haight Ashbury. BeauSoleil knew the house soundman, Brent Dangerfield, and was friendly with the theater’s owners. The first real concert at the venue was a special evening set for the autumnal equinox. Along with well-known San Francisco musical acts such as The Charlatans and The Congress of Wonders, the show would also feature the live debut of The Magick Powerhouse of Oz. The atmosphere would be enhanced with the help of two lightshow companies, one of which would be projecting Lucifer Rising footage as well as a vintage print of the original Wizard of Oz during the show. Between sets by The Magick Powerhouse, Anger was to perform a Crowleyan ritual to celebrate the pagan holiday. Expectations and emotions were running high before the event, but no one could have predicted that the equinoctial extravaganza would be an explosive flashpoint in the disintegration of Anger’s and BeauSoleil’s working relationship.

The audience turnout was smaller than hoped for, and The Charlatans had been dropped from the bill, but The Magick Powerhouse’s debut performance went smoothly and was well-received. The same cannot be said for Anger’s solo magick ritual. Earlier that evening he had made the decision to ingest a quantity of LSD, which proved unwise when technical problems arose with a backing tape during the ritual itself, and the addled Anger had a veritable meltdown on stage. Disoriented and delirious, he smashed a cane and inadvertently wounded a member of the audience—an editor at the San Francisco Oracle underground newspaper—with one of its jagged shards. This embarrassing performance caused a rift to develop between BeauSoleil and Anger, and their paths parted the following morning. There were some hard feelings, and Anger subsequently accused BeauSoleil of having stolen the only existing copy of his work in progress. Charles Perry gives a brief account of the Equinox concert fiasco in his book The Haight Ashbury. His retelling is largely based on convoluted hearsay, and he exaggerates the “satanic” focus of the event, but the following sentences are probably accurate: “At the end of the show Van Meter [one of the lightshow technicians] returned the film to Anger, who handed it to someone else for safekeeping so he could leave for a post-invocation party. Anger had called it ‘my first religious film’; to non-satanists it had seemed to be merely shots of Bobby Beausoleil in weightlifter poses. During the night the film was stolen, and the culprit was widely assumed to be Beausoleil.”

The audience turnout was smaller than hoped for, and The Charlatans had been dropped from the bill, but The Magick Powerhouse’s debut performance went smoothly and was well-received. The same cannot be said for Anger’s solo magick ritual. Earlier that evening he had made the decision to ingest a quantity of LSD, which proved unwise when technical problems arose with a backing tape during the ritual itself, and the addled Anger had a veritable meltdown on stage. Disoriented and delirious, he smashed a cane and inadvertently wounded a member of the audience—an editor at the San Francisco Oracle underground newspaper—with one of its jagged shards. This embarrassing performance caused a rift to develop between BeauSoleil and Anger, and their paths parted the following morning. There were some hard feelings, and Anger subsequently accused BeauSoleil of having stolen the only existing copy of his work in progress. Charles Perry gives a brief account of the Equinox concert fiasco in his book The Haight Ashbury. His retelling is largely based on convoluted hearsay, and he exaggerates the “satanic” focus of the event, but the following sentences are probably accurate: “At the end of the show Van Meter [one of the lightshow technicians] returned the film to Anger, who handed it to someone else for safekeeping so he could leave for a post-invocation party. Anger had called it ‘my first religious film’; to non-satanists it had seemed to be merely shots of Bobby Beausoleil in weightlifter poses. During the night the film was stolen, and the culprit was widely assumed to be Beausoleil.”

BeauSoleil has always disputed Anger’s claim that he stole the Lucifer Rising reels. He asserts that very little film actually existed outside of a few strips of test footage, and that Anger was simply making up stories to keep impatient investors at bay who were demanding to know why the film had not been completed. (Curiously, footage of BeauSoleil and The Magick Powerhouse of Oz did resurface in a short Anger feature called Invocation of My Demon Brother, released in 1969.) The fate of the Lucifer Rising film reels notwithstanding, The Magick Powerhouse of Oz’s debut and swan song had come and gone in the same evening. And within a matter of weeks, the protagonists in the Lucifer Rising saga had scattered. BeauSoleil was en route to southern California, burned out on the madness of San Francisco; a short time later Anger left the U.S.A. altogether for London. Before his transatlantic move Anger published a full-page fake death notice for himself in the underground paper The Berkeley Barb. Anger’s faux obituary seemed a recognition of darker things on the horizon—the Summer of Love had faded, and an era that had barely just begun was already coming to a painful close.

The Magick Powerhouse of Oz imploded upon BeauSoleil’s departure from San Francisco, and his shot at an underground acting career was over. But Anger still had hopes to finish Lucifer Rising, and after settling down in London he commissioned Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page, a fervent Crowleyite, to do the soundtrack. This plan would eventually flounder when Page was unable to deliver more than twenty-eight minutes of music.

Caged for an ill-conceived 1969 murder, first in San Quentin, and later in Tracy State Prison, BeauSoleil’s creative impulses could not be squelched despite his repressive surroundings. With diligence he was able to set up an inmate music program at the latter institution in the early 1970s. Through all these years, Lucifer Rising still persistently occupied his thoughts. As he explained: “At some point I had heard that [Kenneth] was again getting ready to do Lucifer Rising. It was still his pet project and he was getting ready to finish it … I decided I’d talk to him about it, because I’d always felt, ever since our parting of ways in 1967, that this was unfinished business. I still believed in the concept as it had originally been described to me: heralding the dawn of a new age, ritualizing that process, the mythological aspects, and all of that. It spoke to me, it resonated with me. I wanted to complete the project as I felt it was unfinished, and I don’t like loose ends.”

Caged for an ill-conceived 1969 murder, first in San Quentin, and later in Tracy State Prison, BeauSoleil’s creative impulses could not be squelched despite his repressive surroundings. With diligence he was able to set up an inmate music program at the latter institution in the early 1970s. Through all these years, Lucifer Rising still persistently occupied his thoughts. As he explained: “At some point I had heard that [Kenneth] was again getting ready to do Lucifer Rising. It was still his pet project and he was getting ready to finish it … I decided I’d talk to him about it, because I’d always felt, ever since our parting of ways in 1967, that this was unfinished business. I still believed in the concept as it had originally been described to me: heralding the dawn of a new age, ritualizing that process, the mythological aspects, and all of that. It spoke to me, it resonated with me. I wanted to complete the project as I felt it was unfinished, and I don’t like loose ends.”

Upon hearing a demo tape that BeauSoleil sent out to him from prison, Anger was impressed enough to fire Jimmy Page and bring BeauSoleil back into the fold to complete the soundtrack. Through the help of Dr. Minerva Bertholf, an elderly teacher at the prison, and a cooperative warden named R. M. Rees, BeauSoleil was granted approval for the project and permission to receive materials he needed in order to build keyboards and special effects generators. The moniker for BeauSoleil’s band of prison musicians he enlisted to perform the newly composed score was The Freedom Orchestra. It took a number of years before the recordings were completed, which is unsurprising given the adverse circumstances. The budget for the soundtrack was a little over $3,000. With these limited funds, BeauSoleil had to build an entire recording studio from scratch. As he explained, “In order to stretch the money far enough, I got into electronics and into building equipment myself. Necessity is the mother of invention, and this was the only way that I could provide myself and the other musicians involved with the instruments that would allow us to create a soundtrack that had some timbral variations, and not just guitars played through guitar amps. I had this grandiose concept in my head of how I wanted the score to sound. I didn’t want it to sound like it was made on a bunch of toys, yet that’s what it was, really! Still, we did some pretty amazing things.” BeauSoleil had to do the final mixing, sequencing, and tape splicing in his tiny cell, where he had been allowed to move the requisite equipment, utilizing headphones and working by night. It was only in 1980, more than thirteen years after first beginning work on Lucifer Rising, that Anger was finally able to publicly screen the finished film with its proper soundtrack at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

What can be heard on the first disc of the present reissue is the full soundtrack to Lucifer Rising as recorded by Bobby BeauSoleil and the Freedom Orchestra circa 1977–79. In the quarter-century since then, its dynamic power and emotional impact remain undiminished. It not only perfectly suits the mood of Anger’s film, but also even seems to have been scored precisely to coincide with certain visual images that occur onscreen. In fact, BeauSoleil and the band had only been able to view a partial slash print of Lucifer Rising before working on the music, and such correspondences were fortuitous accidents. “Given the way it was put together, it was serendipitous that they coincided so well. And there were a number of places that anyone watching would think must have been orchestrated or intentional, but they weren’t. That was part of the ‘magical spell’ that Kenneth felt was being worked. The creation of the entire film was an invocation or spell for him. The happenstance of it is an element that he chose to include—which I can appreciate, as an improvisational artist myself,” comments BeauSoleil.

What can be heard on the first disc of the present reissue is the full soundtrack to Lucifer Rising as recorded by Bobby BeauSoleil and the Freedom Orchestra circa 1977–79. In the quarter-century since then, its dynamic power and emotional impact remain undiminished. It not only perfectly suits the mood of Anger’s film, but also even seems to have been scored precisely to coincide with certain visual images that occur onscreen. In fact, BeauSoleil and the band had only been able to view a partial slash print of Lucifer Rising before working on the music, and such correspondences were fortuitous accidents. “Given the way it was put together, it was serendipitous that they coincided so well. And there were a number of places that anyone watching would think must have been orchestrated or intentional, but they weren’t. That was part of the ‘magical spell’ that Kenneth felt was being worked. The creation of the entire film was an invocation or spell for him. The happenstance of it is an element that he chose to include—which I can appreciate, as an improvisational artist myself,” comments BeauSoleil.

Lucifer Rising may function abstractly as invocation on the part of the director, but it also visually documents the interior and exterior worlds—the microcosm and macrocosm—of the ceremonial magician. Scenes of introspective psychedelic imagery and claustrophobic interior ritual chambers alternate with expansive, epic outdoor location shots at occult “power points” like the Externsteine in Germany (a mysterious configuration of towering natural rock formations that has been used as a cultic site for millennia), Stonehenge, and the awe-inspiring temples of Luxor and Karnak in Egypt. The startling juxtaposition of these extreme points of perspective, and the tension between them, is a key to the film’s imaginable beauty.

A similar underlying dialectic is present in BeauSoleil’s soundtrack: a magically potent transcendence of opposites arises through the very circumstances of the music’s manifestation. Composed and recorded behind iron bars in a claustrophobic concrete dungeon, the resulting soundscapes expand and flow liberatingly outward with an almost limitless reach. The mind that conceived these sounds is a kindred spirit to the perfect tiny reptile that breaks out of its shell at the beginning of Anger’s film, the herald of a new age. And if the listener detects a dark undercurrent here in spite of the “solar” theme, it is no wonder. During the period of these recordings Tracy Prison was an extremely ugly and volatile place, marked by daily murders and an unprecedented degree of antagonism among the inmates. But where others might have wallowed in the misery of their surroundings, BeauSoleil used the creative energy of music to effectively transmute and transcend them.

A similar underlying dialectic is present in BeauSoleil’s soundtrack: a magically potent transcendence of opposites arises through the very circumstances of the music’s manifestation. Composed and recorded behind iron bars in a claustrophobic concrete dungeon, the resulting soundscapes expand and flow liberatingly outward with an almost limitless reach. The mind that conceived these sounds is a kindred spirit to the perfect tiny reptile that breaks out of its shell at the beginning of Anger’s film, the herald of a new age. And if the listener detects a dark undercurrent here in spite of the “solar” theme, it is no wonder. During the period of these recordings Tracy Prison was an extremely ugly and volatile place, marked by daily murders and an unprecedented degree of antagonism among the inmates. But where others might have wallowed in the misery of their surroundings, BeauSoleil used the creative energy of music to effectively transmute and transcend them.

In BeauSoleil’s compositions the elemental magic of natural forces is dramatically evident: the synesthetic sounds of eruption; of fluid, molten rock; of piercing sunlight and thermal violence. But all this is subtly cloaked in the black ceremonial robe of the magician, canopied by the dark dome of the night sky, underpinned by the shadow-realm of the underworld. It is simultaneously a eulogy of profound sadness and a surging, victorious expression of hope.

When I first made contact with Bobby BeauSoleil many years ago, initially it was in order to interview him for a magazine feature about his musical past, present, and future. Around the same time I was often a visitor to the home of Mark McCloud, an authority on the Psychedelic Sixties and curator of the “Museum of Illegal Art” in San Francisco. His private historical museum houses the world’s most extensive collection of framed LSD blotter, along with a vast array of psychedelic artwork, posters, and ephemera. Whenever the subject of my contact with BeauSoleil came up, McCloud would respond in his inimitable drawl with the same exhortation: “Ask Bobby to tell you where the Magick Powerhouse tape is hidden.”

At an opportune moment I did finally pop the question to BeauSoleil. With utmost sincerity he insisted that no such tape existed, there was no basis to the rumor. McCloud refused to believe this and, as it turned out, his suspicions were vindicated a few years later. David LaFlamme happened to have a box of tapes stored at his house, which had been entrusted to him by BeauSoleil on that fateful day in 1967 when he fled San Francisco for Los Angeles. LaFlamme had promised to hold onto the box for BeauSoleil until he next saw him. He had stored it away and forgotten about it. Rediscovered in that box, more than thirty years later, were not just rehearsal and live recordings by The Orkustra, but also a mysterious tape labeled “Lucifer Rising.”

At an opportune moment I did finally pop the question to BeauSoleil. With utmost sincerity he insisted that no such tape existed, there was no basis to the rumor. McCloud refused to believe this and, as it turned out, his suspicions were vindicated a few years later. David LaFlamme happened to have a box of tapes stored at his house, which had been entrusted to him by BeauSoleil on that fateful day in 1967 when he fled San Francisco for Los Angeles. LaFlamme had promised to hold onto the box for BeauSoleil until he next saw him. He had stored it away and forgotten about it. Rediscovered in that box, more than thirty years later, were not just rehearsal and live recordings by The Orkustra, but also a mysterious tape labeled “Lucifer Rising.”

This contained the only audio document ever made of The Magick Powerhouse of Oz. It was live room recording that had been done in the Straight Theater, engineered by Brent Dangerfield. BeauSoleil was as surprised as anyone to learn of its existence. It is an extended and quasi-improvised jam session that contains the primitive seeds of the Lucifer Rising soundtrack—or at least of how it might have sounded had it been completed in 1967. Already the sinewy, cascading theme can be heard which would become an even more prominent leitmotif many years later in The Freedom Orchestra’s version. Thanks to modern studio technology, and careful remastering work by BeauSoleil and Robert Ferbrache, these vintage recordings can now be heard just as they were originally meant to sound.

Together, these discs represent the definitive document of Bobby BeauSoleil’s contribution to Lucifer Rising. Make no mistake, this is groundbreaking work: the result of the collaborative interaction of two artists working under radically different conditions. By way of their fractious relationship, and their stalwart allegiance to their individual and united artistic visions, Kenneth Anger and Bobby BeauSoleil managed in the end to craft a peerless work of dark psychedelia, a volcanic expression of triumphant spiritual freedom. The route leading to its eventual manifestation was treacherous and serpentine, a passageway oftentimes obscured in darkness and shadow. Yet through it all radiant Lucifer, their patron deity, managed to somehow keep them on course. It is high time that the real history of the Lucifer Rising soundtrack has resurfaced and come to light.

Together, these discs represent the definitive document of Bobby BeauSoleil’s contribution to Lucifer Rising. Make no mistake, this is groundbreaking work: the result of the collaborative interaction of two artists working under radically different conditions. By way of their fractious relationship, and their stalwart allegiance to their individual and united artistic visions, Kenneth Anger and Bobby BeauSoleil managed in the end to craft a peerless work of dark psychedelia, a volcanic expression of triumphant spiritual freedom. The route leading to its eventual manifestation was treacherous and serpentine, a passageway oftentimes obscured in darkness and shadow. Yet through it all radiant Lucifer, their patron deity, managed to somehow keep them on course. It is high time that the real history of the Lucifer Rising soundtrack has resurfaced and come to light.

—Michael Moynihan

Vernal Equinox, 2004

[Text © 2004 Michael Moynihan. May not be reproduced without permission. A slightly longer version of this essay appears as the liner notes to the Lucifer Rising Suite box set.]

© 2014 Bobby BeauSoleil. All Rights Reserved. Beth Hall Designs | Images are copyrighted to their respective owners